Lecture Notes 5: Logical Agent and First-Order Logic

The solution derived from search technique is limited and in inflexible sense. For example, the agent does not know that the tic-tac-toe games cannot occupy two or more symbols in one square. In route finding agent, the agent does not know that the distance can not be negative. The agent actually only choose based on what it knows about the current state and can list all possible concrete states/solution.

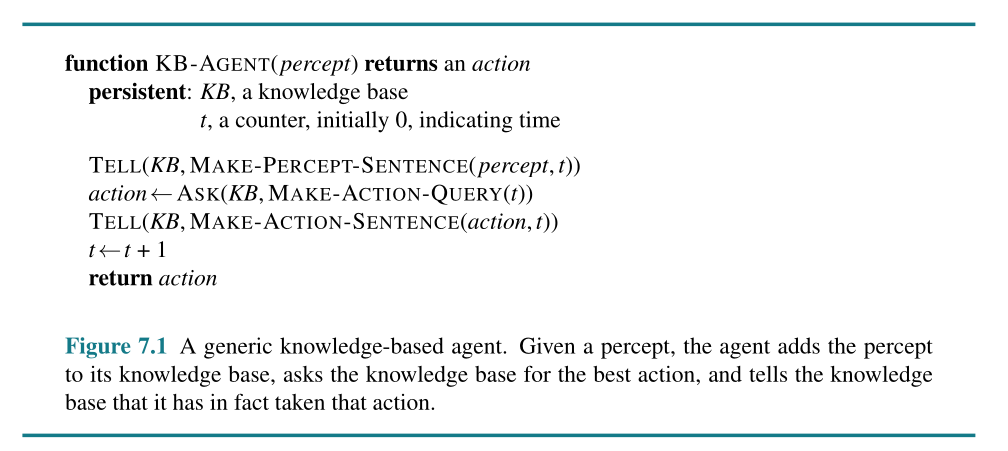

Above is an example of the generic knowledge-based agent. The knowledge based is represented in the set of sentences that can be inferred (the terms sentence here is a bit technical and not identical with english or bahasa)

“Each sentence is expressed in a language called a knowledge representation language and represents some assertion about the world. When the sentence is taken as being given without being derived from other sentences, we call it an axiom.”

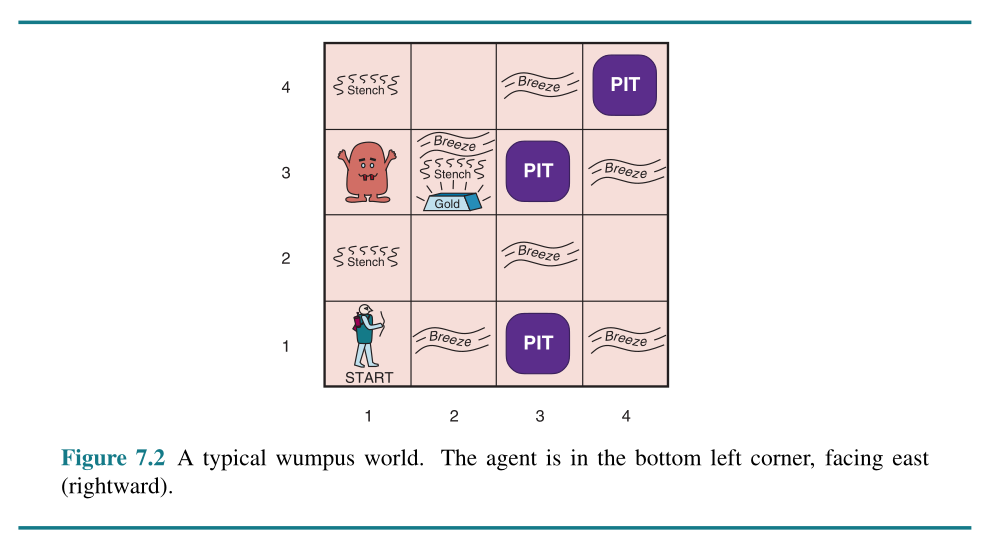

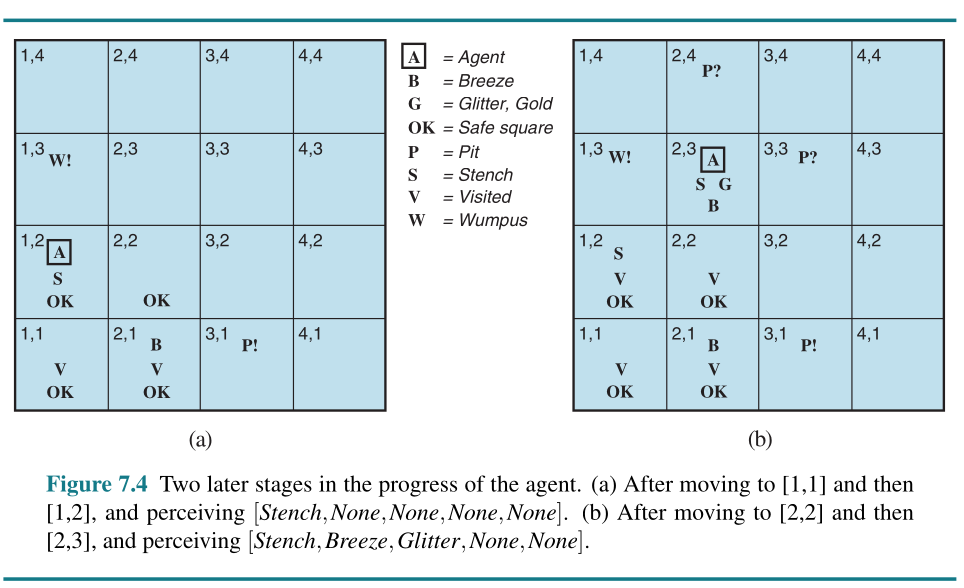

The Wumpus World

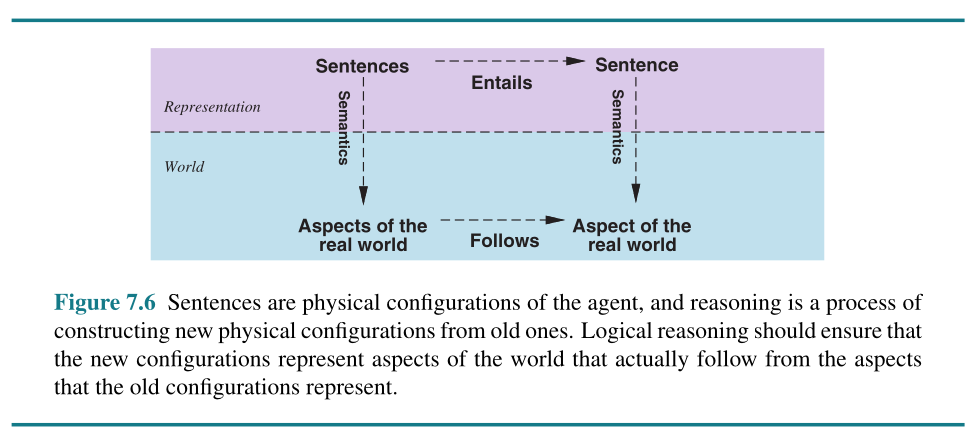

Logic

Entailment

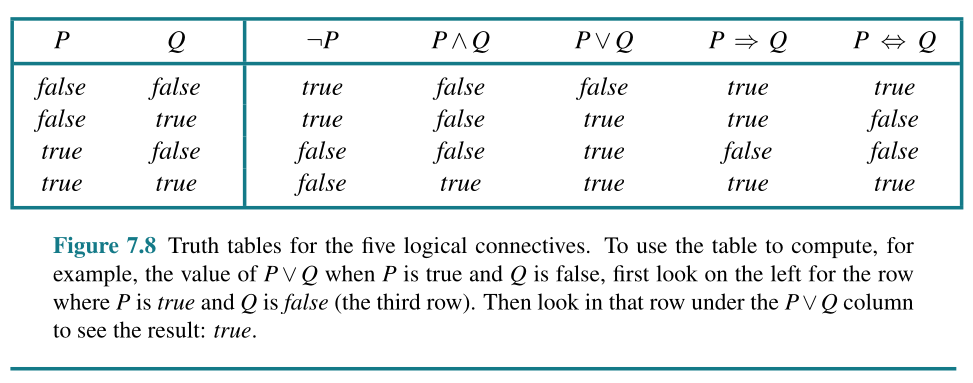

Propositional Logic

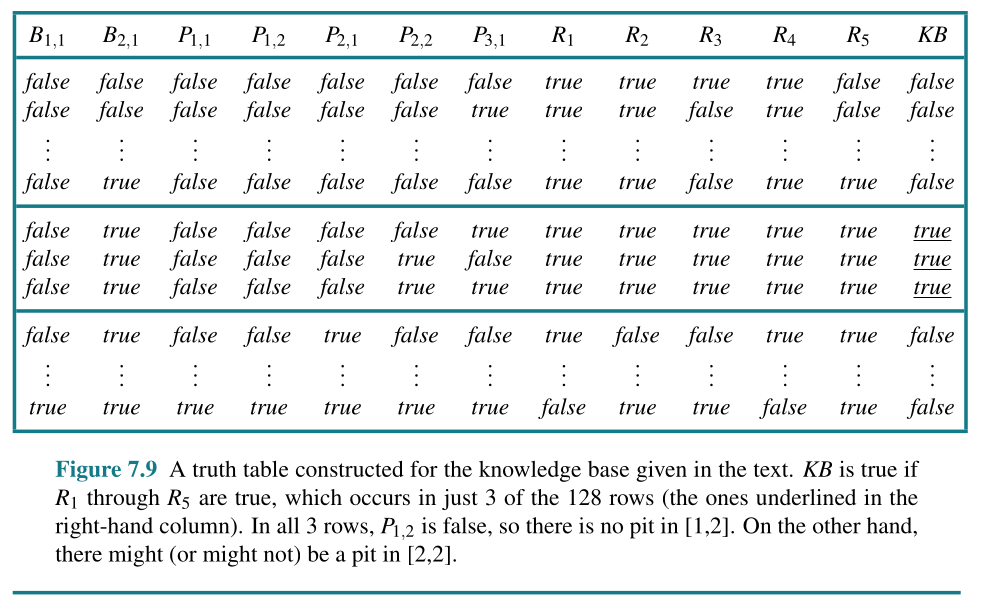

A simple knowledge based and inference procedure

- Px,y is true if there is a pit in [x, y].

- Wx,y is true if there is a wumpus in [x, y], dead or alive.

- Bx,y is true if there is a breeze in [x, y].

- Sx,y is true if there is a stench in [x, y].

- Lx,y is true if the agent is in location [x, y].

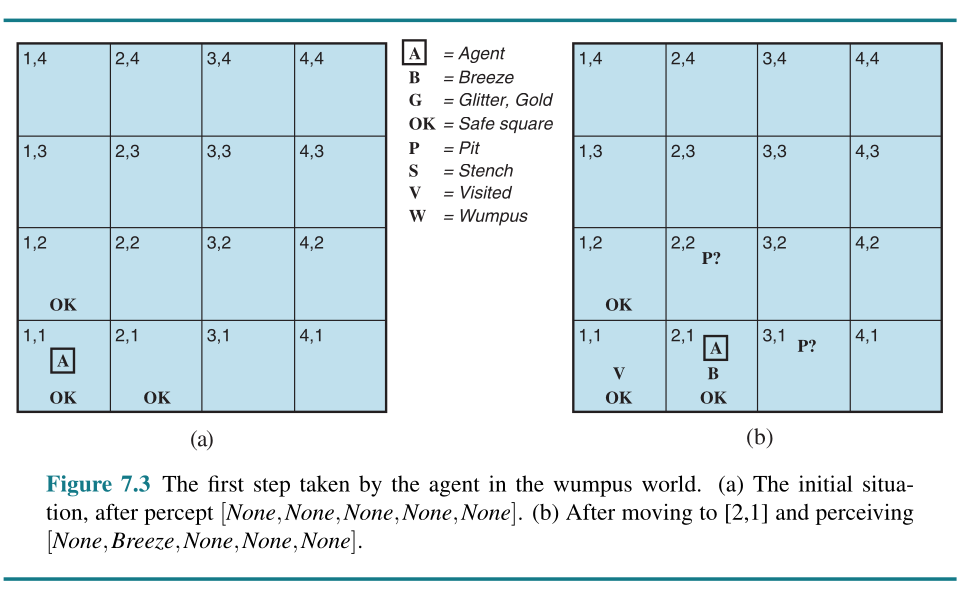

There is no pit in [1,1]:

R1 : ¬P1,1 .

A square is breezy if and only if there is a pit in a neighboring square. This has to be stated for each square; for now, we include just the relevant squares:

R2 :B1,1 ⇔ (P1,2 ∨ P2,1 ) .

R3 :B2,1 ⇔ (P1,1 ∨ P2,2 ∨ P3,1 ) .

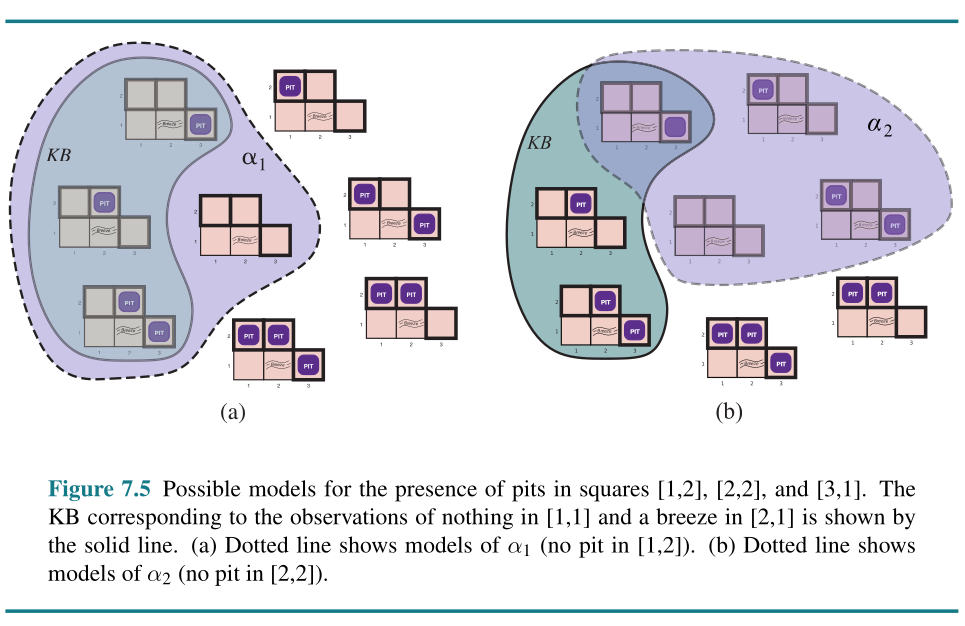

The preceding sentences are true in all wumpus worlds. Now we include the breeze percepts for the first two squares visited in the specific world the agent is in, leading up to the situation in Figure 7.3(b).

R4 : ¬B1,1 .

R5 : B2,1 .

How a simple inference procedure?

First-Order Logic (FOL)

| Language | Ontological Commitment (What exists in the world) | Epistemological Commitment (What an agent believes about facts) |

|---|---|---|

| Propositional logic | facts | true/false/unknown |

| First-order logic | facts, objects, relations | true/false/unknown |

| Temporal logic | facts, objects, relations, times | true/false/unknown 2C |

| Probability theory | facts | degree of belief ∈ [0, 1] |

| Fuzzy logic | facts with degree of truth ∈ [0, 1] | known interval value |

Syntax and Semantics of First-Order Logic

Terms

“A term is a logical expression that refers to an object. Constant symbols are terms, but it is not always convenient to have a distinct symbol to name every object. In English we might use the expression “King John’s left leg” rather than giving a name to his leg. This is what function symbols are for: instead of using a constant symbol, we use LeftLeg(John).”

Atomic Sentences

“Now that we have terms for referring to objects and predicate symbols for referring to relations, we can combine them to make atomic sentences that state facts. An atomic sentence (or atom for short) is formed from a predicate symbol optionally followed by a parenthesized list of terms, such as Brother(Richard, John). This states, under the intended interpretation given earlier, that Richard the Lionheart is the brother of King John. Atomic sentences can have complex terms as arguments. Thus,”

Married(Father(Richard), Mother(John))

Complex Sentences

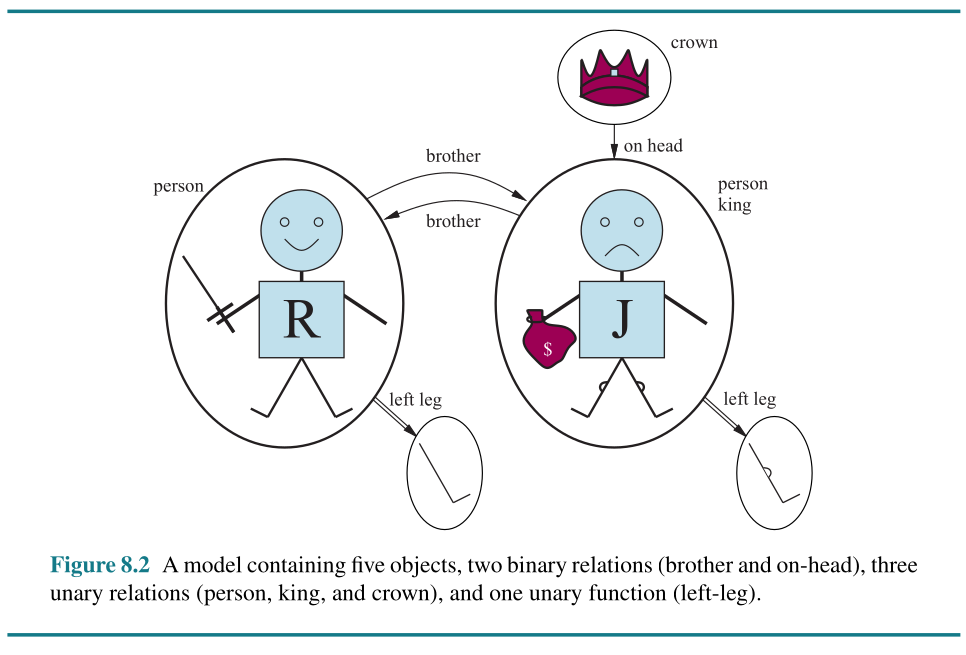

“We can use logical connectives to construct more complex sentences, with the same syntax and semantics as in propositional calculus. Here are four sentences that are true in the model of Figure 8.2 under our intended interpretation:”

¬Brother(LeftLeg(Richard), John)

Brother(Richard, John) ∧ Brother(John, Richard)

King(Richard) ∨ King(John)

¬King(Richard) ⇒ King(John)

Quantifiers

∀x King(x) ⇒ Person(x).

∃x Crown(x) ∧ OnHead(x, John)

∀x ∀y Brother(x, y) ⇒ Sibling(x, y)

∀x,y Sibling(x, y) ⇔ Sibling(y, x).

∀x ∃y Loves(x, y). #Everybody loves somebody

∀x ∃y Loves(x, y). #There is someone who loves by everyone

∀x ¬Likes(x, Parsnips) is equivalent to ¬∃x Likes(x, Parsnips).

∀x Likes(x, IceCream) is equivalent to ¬∃x ¬Likes(x, IceCream).

¬∃x P ≡ ∀x ¬P

¬∀x P ≡ ∃x ¬P

∀x P ≡ ¬∃x ¬P

∃x P ≡ ¬∀x ¬P

¬(P ∨ Q) ≡ ¬P ∧ ¬Q

¬(P ∧ Q) ≡ ¬P ∨ ¬Q

P∧Q ≡ ¬(¬P ∨ ¬Q)

P∨Q ≡ ¬(¬P ∧ ¬Q) .

FOL Example

TELL(KB, King(John))

TELL(KB, Person(Richard))

TELL(KB, ∀ x King(x) ⇒ Person(x))

ASK(KB, King(John))

ASK(KB, Person(John))

ASK(KB, ∃x Person(x))

ASKVARS(KB, Person(x))

Knowledge Engineering in FOL

The words below are literally taken from the original book:

- “Identify the questions. The knowledge engineer must delineate the range of questions that the knowledge base will support and the kinds of facts that will be available for each specific problem instance. For example, does the wumpus knowledge base need to be able to choose actions, or is it required only to answer questions about the contents of the environment? Will the sensor facts include the current location? The task will determine what knowledge must be represented in order to connect problem instances to answers. This step is analogous to the PEAS process for designing agents in Chapter 2.”

- Assemble the relevant knowledge. The knowledge engineer might already be an expert in the domain, or might need to work with real experts to extract what they know—aprocess called knowledge acquisition. At this stage, the knowledge is not represented formally. The idea is to understand the scope of the knowledge base, as determined by the task, and to understand how the domain actually works.

- “Decide on a vocabulary of predicates, functions, and constants. That is, translate the important domain-level concepts into logic-level names. This involves many questions of knowledge-engineering style. Like programming style, this can have a significant impact on the eventual success of the project. For example, should pits be represented by objects or by a unary predicate on squares? Should the agent’s orientation be a function or a predicate? Should the wumpus’s location depend on time? Once the choices have been made, the result is a vocabulary that is known as the ontology of the domain. The word ontology means a particular theory of the nature of being or existence. The ontology determines what kinds of things exist, but does not determine their specific properties and interrelationships.”

- “Encode general knowledge about the domain”. The knowledge engineer writes down the axioms for all the vocabulary terms. This pins down (to the extent possible) the meaning of the terms, enabling the expert to check the content. Often, this step reveals misconceptions or gaps in the vocabulary that must be fixed by returning to step 3 and iterating through the process.

- “Encode a description of the problem instance. If the ontology is well thought out, this step is easy. It involves writing simple atomic sentences about instances of concepts that are already part of the ontology. For a logical agent, problem instances are supplied by the sensors, whereas a “disembodied” knowledge base is given sentences in the same way that traditional programs are given input data.”

- “Pose queries to the inference procedure and get answers. This is where the reward is: we can let the inference procedure operate on the axioms and problem-specific facts to derive the facts we are interested in knowing. Thus, we avoid the need for writing an application-specific solution algorithm.”

- “Debug and evaluate the knowledge base. Alas, the answers to queries will seldom be correct on the first try. More precisely, the answers will be correct for the knowledge base as written, assuming that the inference procedure is sound, but they will not be the ones that the user is expecting. For example, if an axiom is missing, some queries will not be answerable from the knowledge base. A considerable debugging process could ensue.”

Logic Programming (Python Library): miniKanren

from kanren import Relation, facts, run, var, conde

# create relations

parent = Relation()

male = Relation()

female = Relation()

# facts: parent(Parent, Child)

facts(parent,

('john', 'mary'),

('anna', 'mary'),

('john', 'andy'),

('mary', 'susan'))

facts(male, ('john',))

facts(female, ('anna',), ('mary',), ('susan',))

# Query: grandparent(X, 'susan') i.e. exists Y such that parent(X,Y) and parent(Y,'susan')

X = var()

Y = var()

grandparents = run(0, X, conde((parent(X, Y), parent(Y, 'susan'))))

print("Grandparents of susan:", grandparents)

# Query: siblings of 'mary' (share a parent)

S = var()

P = var()

# find S where exists P: parent(P, S) and parent(P, 'mary') and S != 'mary'

siblings = run(0, S,

conde((parent(P, S), parent(P, 'mary'))))

print("Raw siblings (may include mary):", siblings)

print("Raw siblings:", set([x for x in siblings if x not in ['mary']]))